A year after the 7 October massacre, Spanish-Israeli relations are at their lowest ebb

Through a mixture of ignorance, posturing, and, in many cases, raw antisemitism, Pedro Sánchez and his allies have undone decades of work.

‘Truth does not become more true by virtue of the fact that the entire world agrees with it, nor less so even if the whole world disagrees with it’

Rabbi Moses ben Maimon – Maimónides (c.1135-1208)

A year ago today, a coordinated Hamas-led attack on Israel left a trail of destruction, some 1,200 people killed, most of them civilians, and several other thousands injured. Many Israelis remain hostages of the terrorist group. On 19 October 2023, the European Parliament passed a resolution of condemnation against this atrocious act of terrorism. 500 MEPs voted in favour of the motion, with a small group of 21 voting against it. Of those, four were Spanish MEPs. A month later, two of them, Sira Rego and Ernest Urtasun, were named Senior Ministers of the Spanish government by Pedro Sánchez. In May of this year, Spain, together with Ireland and Norway, formally recognised the “State of Palestine”.

Shortly after, Vice-President Yolanda Díaz concluded a rally by shouting the anti-Israeli slogan “from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free”. A few weeks passed and, in June, Spain became the first European nation to join South Africa’s International Court of Justice case against Israel, which accuses the Jewish state of genocide. In July, Spain’s Defence Minister Margarita Robles explicitly alleged that Israel was guilty of genocide, whilst complaining of NATO’s “double standards” vis-à-vis Ukraine.

The optics arising from the above sequence of events tell their own story. Over the past twelve months, Spain has been the flag bearer of the most uncompromising anti-Israeli stances in the Western world. This has resulted in an exchange of hostile declarations between both governments, followed by the summoning of the ambassadors in Madrid and Tel Aviv. Spanish-Israeli bilateral relations, which only began in 1986, are now at their lowest ebb. Meanwhile, Hamas has praised Spain’s “clear, bold stance” on the conflict. A second iteration of the Conference of Madrid of 1991, which led to a peace treatise, would be unthinkable today: Spain has unilaterally abandoned any credibility as a potential broker of an agreement between the belligerent parties, by unequivocally adopting a defiant anti-Israeli rhetoric that can only be explained by ideological entrenchment.

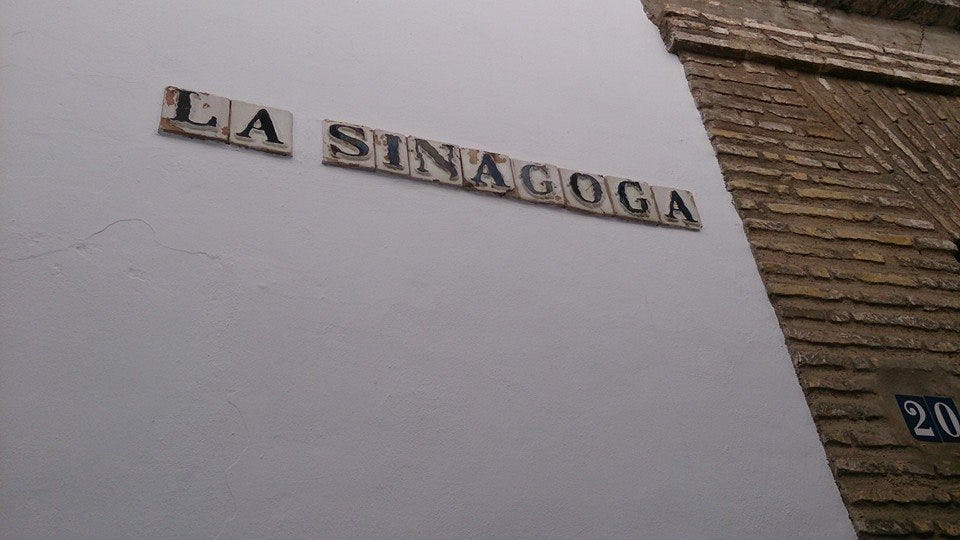

In the early 90s, Spain gained considerable political capital by presenting itself as a historical bridge between Jews and Muslims, whilst appealing to an idealised account of its own past. Having grappled with its own ghosts, Spain’s young democracy was seen as an example of orderly, rule-based reconciliation against the odds —one that could be exported to other troubled parts of the world. Al-Andalus (Muslim Iberia) and Sefarad (Jewish Spain) were also an inspiring role model for coexistence that could be applied to the Middle East. Some of that naïve optimism remained when, in 2009, US President Barack Obama delivered a well-meaning speech at the University of Cairo in which he made historically false claims about Spain’s past. Obama presented Al-Andalus as an example for the present by quoting decontextualised ideas from María Rosa Menocal’s landmark book of 2002 The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain.

In 2015, the Spanish Parliament passed a bill granting Spanish (and therefore European) citizenship to all descendants of the Sephardic diaspora. This was a symbolic repeal of the Alhambra Decree of 1492, which forced Spain’s Jews to choose between conversion and exile. Some 125,000 people took advantage of the law, which was aimed at “correcting a historical wrong”, reconciling Spain with its Jewish past, and recognising Jewish contributions to Spanish and European history. The Duke of Medina-Sidonia spoke of the “shameful” actions of his ancestors in a ceremony with Spain’s Jewish communities.

The words of royal chronicler Andrés Bernáldez, in his account of the expulsion of 1492, resonated again in 2015:

And they [the Spanish Jews] left the land of their ancestors and their birth, the young and the old, some on foot, others riding their donkeys (…). They walked the roads with sadness and difficulty, some of them falling, others getting up from the floor, others dying, others being born, others falling ill. There was no good Christian who could look the other way and not suffer their pain. And everyone, wherever they went, begged them to baptise and stay. And some, in their unspeakable pain, converted and stayed, but very few of them. The Rabbis tried to lift their spirits. Young men and women sang and played the drums to encourage their people. And this is how they left Spain and reached the seaports that were assigned to them.

These acts of historical restitution were not to the detriment of Spain’s traditional ties with the Arab world. They were, on the other hand, a positive deployment of soft power. Remembrance of the Sephardim also served to integrate the Israeli Academy of Ladino / Judeo-Spanish into the network of Royal Academies of the Spanish language across the world. Historicist revival also brought with it a timely and sobering reminder of the fate of one of the biggest Sephardic communities of the 20th century, that of Thessaloniki, most of whose members perished in the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Through a mixture of ignorance, posturing, and, in many cases, raw antisemitism, Pedro Sánchez and his allies have undone decades of work. They have indulged in explicit denial of Israel’s right to exist; they have earned the enthusiastic praise of Islamist terrorists; their supporters’ social media have caricatured Judaism as the engine of an alleged genocide sponsored by global capitalism; they have turned a conscious blind eye on the thousands of Iran-sponsored rockets raining over Israeli civilians; they appear oblivious of the fact that Israel’s existence is directly dependent on an Iron Dome that is not an expensive extravagance but the last line of defence preventing Hamas and Hezbollah from wiping out all Jews, “from the river to the sea”.

Netanyahu’s government shall pass, as shall Sánchez’s, but Israel is unlikely to forget any time soon that, in the year that followed the worst massacre of Jews since World War II, Spain was again the hostile and bitter “uttermost West” decried by Judah ha-Levi when longing for a return to Jerusalem in his poem “My heart is in the East”. Another Sephardic thinker, the ever-empathetic and rationalistic Maimónides, defined evil as, quite simply, “the absence of good”. In both pragmatic and moral terms, this is also the best definition of Spain’s actions in the past twelve months: a compendium of nihilistic and militant “absences of good”.

Carlos Conde Solares’s forthcoming book is entitled The Last of the Almojarifes: Jewish Scapegoats of the Crown of Castile.